What did Jo March mean when she said she wanted to create something “spendid?”

What did Jo March mean when she said she wanted to create something “spendid?”

Perhaps gaining recognition for her writing. Maybe even being hailed as a great writer. Writing a book of artistic merit and universality that would stand the test of time.

Yet we find in Little Women that Jo’s goals would evolve from that solitary act of writing into a communal creation: a school for boys, founded in partnership with her new husband, Professor Bhaer. In the end, I believe she satisfied her desire to create something “splendid.”

Why caused her goals to change?

I’d like to offer my opinion and then I’d love to hear from you!

Here’s my theory.

A necessary act

Writing was a legitimate and necessary creative activity for Jo. It helped her to release the tremendous energy inside of her that otherwise might have expressed itself in negative ways. She had talent and much to share.

Writing was a legitimate and necessary creative activity for Jo. It helped her to release the tremendous energy inside of her that otherwise might have expressed itself in negative ways. She had talent and much to share.

A practical way to help

Never happy to sit on the sidelines, Jo used her writing to help her family in practical ways as they coped with Mr. March’s absence along with poverty. Besides providing money, her stories entertained the others.

A means of retreat

Writing was a means of escape. Holed up in the garret, Jo could avoid dealing with growing up, something with which she was in open rebellion.

She fought vehemently against the idea of the family unit being changed with the addition of boyfriends/husbands (recalling her reaction to Meg and John, and her rejection of Laurie as a husband). As long as the immediate family remained intact, she could continue as she was. Womanhood was a frightening prospect as Jo feared it would restrain her spirit. She was like a wild colt refusing to be broken.

A means of verification

Writing verified Jo as a person when nothing else would. When Amy destroyed Jo’s manuscript it was like Jo herself was burnt to a crisp in the fireplace. I believe Jo perceived Amy’s deed as an act of violence against her very self; therefore the depth of her rage was justified in her own mind, until it put Amy’s own life in peril. It was at this point that Jo’s creative energy (anger being a great force) posed a danger to herself and others.

Writing verified Jo as a person when nothing else would. When Amy destroyed Jo’s manuscript it was like Jo herself was burnt to a crisp in the fireplace. I believe Jo perceived Amy’s deed as an act of violence against her very self; therefore the depth of her rage was justified in her own mind, until it put Amy’s own life in peril. It was at this point that Jo’s creative energy (anger being a great force) posed a danger to herself and others.

A way to avoid the truth

Writing was an act that drew Jo into herself, far away from the real world into that safe place of fantasy which gave her consolation. Sometimes that withdrawal could be beneficial, particularly when her emotions were getting the better of her. But often that withdrawal was an escape from a reality she had to face–she could not remain a child forever.

The turning point

I believe the watershed moment for Jo was in her grief after she lost Beth.

Anyone who has grieved over someone knows that such a time can transform one’s life. Whether that transformation takes you forward in growth or leaves you behind, mired in the mud, is a singular choice.

A new idea of “splendid”

At first, willing to do anything to please the sister she so loved and admired, Jo agreed to Beth’s terms: to leave behind her old ambitions of doing something “splendid” to take on the more noble (and needed) task of caring for her parents. She soon found her promise hard to keep when faced with the prospect of living it out without the physical presence of her sister nearby as example:

“… something like despair came over her when she thought of spending all her life in that quiet house, devoted to humdrum cares, a few small pleasures, and the duty that never seemed to grow any easier. ‘I can’t do i. I wasn’t meant for a life like this, and I know I shall break away and do something desperate if somebody doesn’t come and help me.’ she said to herself, when her first efforts failed and she fell into the moody, miserable state of mind which often comes when strong will have to yield to the inevitable.” (from Chapter 42 of Little Women)

A desire to be good

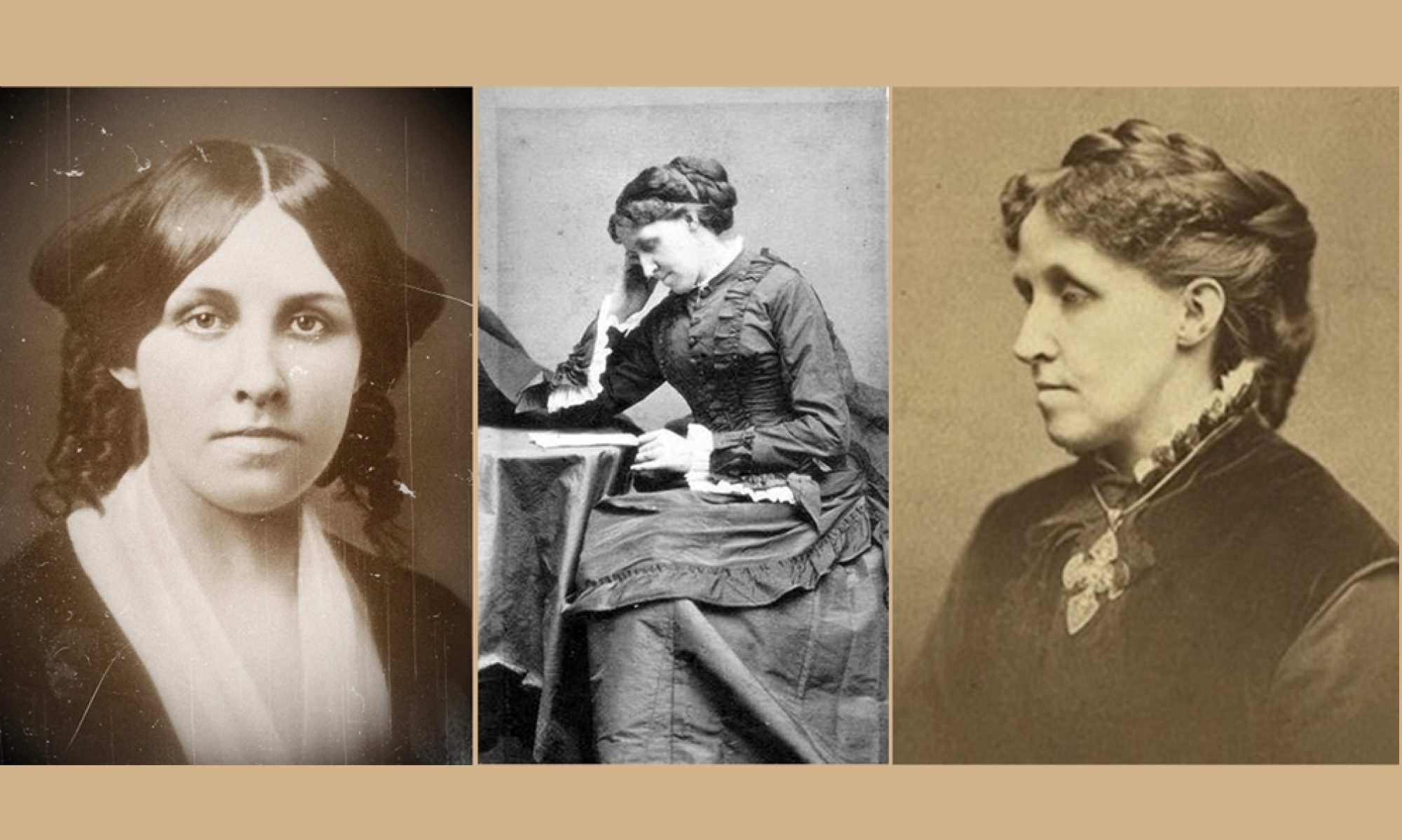

As Jo had lost herself in her writing, she had also been consumed with nursing Beth. Louisa May Alcott herself believed she had a call to nursing that was nearly as strong as her call to be a writer. It was what gave her the courage to become a Civil War nurse. I believe that in nursing Beth (or in Louisa’s case, Lizzie), Jo found a way to be truly virtuous–acting out of sacrificial love for her sister. As much as she desired to live out her creative life, Jo wished also to be good. It was Louisa’s wish too, ingrained in her from her earliest days.

Finding consolation outside of writing

Where once writing provided the consolation, now the counsel of mother and father provided the comfort. Jo was learning to reach out to others rather than retreat into her fantasy world. While she had certainly confided in her parents before, it was more as a child looking for direction. Now she could confide in her parents as an equal, woman to woman, and woman to man:

“Then, sitting in Beth’s little chair close beside him, Jo told her troubles … she gave him entire confidence, he gave her the help she needed, and both found consolation in the act. For the time had come when could talk together not only as father and daughter, but as man and woman, able and glad to serve each other with mutual sympathy as well as mutual love.” (Ibid)

Moving forward

Jo agreed to the process of the grief journey, moving ahead rather than staying behind. She soon grew to find meaning in the mundane household tasks:

“Brooms and dish cloths never could be as distasteful as they once had been, for Beth had presided over both, and something of her housewifely spirit seemed to linger around the little mop and the old bush, never thrown away.” (Ibid)

The beginning of adulthood

In the process, a change took place within Jo, a capacity to long for love outside of her immediate family unit. It was the beginning of her maturing into an adult. Meg saw the potential, urging Jo to consider love:

“It’s just what you need to bring out the tender womanly half of your nature, Jo. You are like a chestnut burr, prickly outside, but silky-soft within, and a sweet kernal, if one can only get at hit. Love will make you show your heart one day, and the rough burr will fall off.” (Ibid)

And indeed, grief would prove to be the tool that would pave the way for “Grief is the best opener” as Louisa writes in chapter 42.

Learning to be herself

Jo tried to justify that living for her parents and not for herself was the “something splendid” that she had desired, but in fact that “something” was missing. In denying herself and living as Beth would, Jo was not living the life to which she was called. The suppression of her creative energy depleted that which fueled her joy, which made life exciting and delicious. It took her mother urging her to write again, even if just to entertain the family, for Jo to find that energy again and bring it back to life. It eventually lead to real success for her as a writer.

Jo tried to justify that living for her parents and not for herself was the “something splendid” that she had desired, but in fact that “something” was missing. In denying herself and living as Beth would, Jo was not living the life to which she was called. The suppression of her creative energy depleted that which fueled her joy, which made life exciting and delicious. It took her mother urging her to write again, even if just to entertain the family, for Jo to find that energy again and bring it back to life. It eventually lead to real success for her as a writer.

Issuing an invitation

And in the end it would be a poem she had written about the four chests in the garret that would issue an invitation (unbeknown to her) to a certain professor to seek out the woman he loved. This time she was ready, having recognized the loneliness in her life:

“I’d like to try all kinds. It’s very curious, but the more I try to satisfy myself with all sorts of natural affections, the more I seem to want. I’d no idea hearts could take in so many. Mine is so elastic, it never seems full now, and I used to be quite contented with my family. I don’t understand it.” (Ibid)

In this admission, Jo embraced adulthood, seeing beyond her tight family unit for the first time.

Lost or found?

Some would argue that Jo in fact lost herself becoming a woman as she did not, in the end, become a writer. Instead, she marries her professor and founds a school for boys with him, using a gift from a most unexpected source–Aunt March’s Plumfield.

Some would argue that Jo in fact lost herself becoming a woman as she did not, in the end, become a writer. Instead, she marries her professor and founds a school for boys with him, using a gift from a most unexpected source–Aunt March’s Plumfield.

Was Jo’s evolution a sell-out by the author?

While it is well known that Louisa would have preferred keeping Jo single and writing, I do not get the sense that Jo was at all unhappy or feeling compromised with her decision to marry or to found the school. It is true that Louisa was compelled by her publisher and her fans to give Little Women a more conventional ending but the evolution of her fictional self from “wild colt” to mature woman felt natural to me. The creative energy Jo had once poured into writing could now be poured into making life better for unfortunate boys. Anyone who has been a teacher knows the creative fire burns bright within, expressing itself in so many ways.

Creativity and community

Jo had evolved from a solitary, strong-willed child who sought escape in her creativity (and who sometimes was controlled by its darker side), to a woman comfortable within a community, using her creativity to make life better for others. It is my belief that the giving away of what we have (and having it accepted gratefully by others) makes makes the creative act worthwhile and satisfying.

Jo had evolved from a solitary, strong-willed child who sought escape in her creativity (and who sometimes was controlled by its darker side), to a woman comfortable within a community, using her creativity to make life better for others. It is my belief that the giving away of what we have (and having it accepted gratefully by others) makes makes the creative act worthwhile and satisfying.

Jo March succeeded in her desire to create something “splendid.”

That’s my theory; what’s yours? Go for it!

Are you passionate about Louisa May Alcott too?

Are you passionate about Louisa May Alcott too?

Subscribe to the email list and never miss a post!

Facebook Louisa May Alcott is My Passion

More About Louisa on Twitter

Your analysis is good and fits with my understanding of Jo. Those who are disappointed by her marriage and later life are, it seems to me, somewhat unrealistic in their expectations. When we are young we dream big dreams and expect life to bend to our will. Most of us have to compromise to some degree. What LMA conveys is that compromise — meeting the world on its own terms — is not a defeat.

Perfect! I could not have said it better myself.

Love the thoughts here, Susan! I’ve also never thought of Jo as “succumbing” or being “repressed” when she marries Friedrich. In fact, it’s the opposite! She marries someone unconventional for love, on her own terms- something many women could only dream of at the time. It’s her idea to start the school and she is the leading force in making that happen. Her independent spirit and creativity is never compromised in becoming a wife and mother; it’s only redirected. If anything, Jo teaches us that we can change our plans, dreams, and goals and still be our essential selves. And I heartily love Jo for that.

A healthy life is one that grows and is open to change. This is one of Jo’s most endearing qualities. In many years, hers was a healthier life than that of her creator. Louisa overcame many things but could not overcome the scars of her upbringing. She was obsessed with having enough money such that it stifled her growth as an artist (and, I believe, her own perception of the true worth of her work – fodder for another post on another day). Could Jo perhaps have been what she hoped she could have been had her growing up years not been so traumatic? Interesting to consider …

I’d say “absolutely!” to all you have written, but I would add that being a great writer doesn’t come all at once…we have to follow Jo into Jo’s boys when she is in her 40s and really reaping the success of all her labors: “A book for girls…she hastily scribbled something about herself and her sisters…there never was a more surprised woman than Josephjne Bhaer when the book became an instant big success…” So the fictional Jo pretty much had it all: a successful school, a successful marriage, successful children and nieces and nephew, rewarding relationships with parents, sisters and brothers-in -law…and neither Jo nor Louisa are forgotten after their deaths.

This is very true! And I’ve yet to read Jo’s Boys (after I finish Rose in Bloom) – I very much look forward to this last chapter in Jo’s life.

Louisa had Jo succumb to what society wanted. A married woman. It’s disappointing she had Jo marry. Its even more disappointing she had Jo marry the old weird professor.

Just like in Victorian society it seems that one can’t be productive or meaningful unless you are married and have kids. That somehow, if you have kids your life is more important and that your impact on society is so much greater.

Louisa’s stance was so strong on the issue of marriage. For Meg to not get married would have seemed absurd. She was the perfect Victorian lady and adhered to society’s demands. Amy wanted marriage too. She always said she would marry someone rich. But Jo, eh she sought a different road, and I truly wish that Alcott would have held firm and kept Jo a happy spinster, writing and being free.

But, I have a different perspective on the world. I am nearly 40 with no children. I have never married and was single the majority of my life. I have my independence and money (well some money, anyway). I, much like Louisa, never wanted to compromise these things and have held firm on my beliefs. It is very disappointing for me that she caved to her publishers and in the end Jo became like every other Victorian housewife.

Understood; your perspective is important as I am married with children. I know too that you are far more knowledgeable about the Victorian era than I (and I envy that!). With all that said, I have to admit I still don’t see Jo’s marriage to the Professor as typical. In Little Men, they act pretty much as equals. Jo does aquiesse to her husband at times but I get the impression she was in fact, still free. Free because she chose her path. As Jill said, she, not the professor, founded the school, using what she was given. She channeled her creative energies into that effort and from I saw in Little Men, it was very satisfying for her.

As a creative myself, my abilities in music and writing have evolved a great deal over the years, beginning with writing as a kid, which then turned into songwriting when I discovered Joni Mitchell. When I had kids I gave up music willingly because I knew how all-consuming music and motherhood could be and I wanted to focus on motherhood. Yet my creativity remained very much alive in the things I did with the kids including creative writing. Now, as I near 60, I have become a profession writer. It took a long time for me to connect the dots and realize that creativity can evolve over the years. I believe I am a much better writer today than I ever could have been when I was younger. It is ripening now, at the right time.

This is what I see in Jo. Louisa most decidedly went down a different road.

I too was disappointed with the fact that Jo ended up marrying Bhaer; I really would have preferred that she remained single and independent.

And Susan, I disagree that the marriage between Jo and Bhaer is one of equals. I think Bhaer is a father figure and teacher to Jo and meant to domesticate her. Sure Bhear’s is not a tyrant or anything; but neither is Laurie nor was Brooke in their marriages to Amy and Meg. So I do think it was a fairly typical marriage of the times. LM and Jo’s Boys are peppered with statements that Bhaer is the head of the household and the leader of the family. This despite the fact that it was her house, her talent, and her wealthy friends that made the school (and later college) possible; where due to the times, Bhaer got to be the teacher and later the president of the college, and where Jo was basically the house mother.

So I agree with Gina. I found it disheartening that Alcott wasn’t able to give Jo a truly alternate and independent life as a strong single woman, instead of letting the publishers dictate her character’s future.

Understood. Many feel the way you do. I think the only issue I’d like to push on a little bit is Louisa’s caving in to her publisher. We all know that Louisa was quite strong-willed but she was undone sometimes by a couple of issues: propriety and money. Louisa was very concerned about appearances despite the fact that she was clearly different. I imagine she was very conflicted in this area. She was so different though that she didn’t even fit into her own family who were completely unconventional. When she became famous with Little Women with which she could fit in: the other famous. Accomplished women, other authors, activists. Her fame opened the door to many like souls.

The other issue that I believe clearly made “caving in” necessary (if not easy) was her obsession with money. Like a true depression-era child, Louisa was deeply scarred by her family’s poverty (and no wonder!). Even when she was truly wealthy it was never enough, thus the need to continue writing “moral pap for the young.”

Therefore I believe that she caved into her publisher of her own free will. It wasn’t the ideal for her for sure, but it was the best compromise.

On a side note, May seemed to be the only Alcott child who was truly free. Although she wanted to act as a proper lady, she also ran away to Europe (with Louisa’s help) and led a bohemian life. She married a much younger man and didn’t even wait to invite her family to come. Life was on her terms.

And if you don’t mind a bit more wandering, while thinking about how I would reply to your comment and in thinking about May, I realized that Louisa wrote that scenario in Little Women about Amy remaining in Europe when Beth was ill and died before it actually happened! In real life May stayed in Europe while her mother was ill and died, several years later. It makes me wonder if Louisa was making some kind of commentary on her sister in writing that scenario … something more to chew on! 🙂

I agree that age does help us become better writers. Of course we must also accept criticism too because without it we will never grow. I will confess now that I am engaged I find that writing is extremely difficult because someone else needs my attention. I don’t have the freedoms I once did, and this is a woman from 2015 talking not 1867.

I will confess its been a long, long time since I read Little Men, so my memory is very fuzzy on that subject. I do agree that Jo starting the school was nice, however, I would have been more impressed had she done it alone. But alas that never was.

Totally off the subject, but have you read The Revelation of Louisa May? It just came out. A young adult book, but I thought it did a great job of capturing Louisa.

This is the eternal struggle for every creative person – balancing that need for solitude versus being out in the world. I often find myself lost in my head in social situations because that’s where I am the happiest. Yet I know I must be social for my own good.

And totally agree about accepting criticism. My editor put me through the wringer and it was incredibly tough. But in the end it was SO worth it because she got the best out of me. You can’t grow without it.

Great conversation!

Would you be interested in reviewing The Revelation of Louisa May? I’d love such a review from you. Let me know.

Interesting post, and a lot to think about. As someone who has always identified with both the fictional Jo and the real Louisa, it’s easy to project myself onto them and look at the two different life paths. The fantasy Louisa really wanted for Jo was for her to be single and successful as a woman writer, similar to J. K. Rowling today. But her publisher and the public wouldn’t have accepted such a radical notion when she finished it in 1869. Women didn’t have any successful role models, women writers were frowned upon by other male writers and the public in general, and it just wasn’t a reality for women at the time. Even though that’s what would satisfy many of us today, it’s just not how life was in New England in the 1860’s. It was definitely more about survival and reputation, too. Louisa chose an extremely hard path by choosing not to marry and surviving by her pen alone. I romanticize that, and many others do, too, but I did freelance write by myself for three years and, even with a husband’s income, was driven into craziness and debilitating worry over money.

The reality is that a husband and a home provides the stability for a woman writer to fully express her creativity without the accompanying worry about money that is so depressing and blocking. Women are privileged in today’s world in a way that a woman like Louisa could only dream of being. There’s also no correlation between a married woman writer’s creativity and a single woman writer’s creativity. My creativity never suffered after I got married – on the contrary, as soon as I married, I was relieved of the burden to exclusively provide my own income myself, and have thrived. Now, I’m on my way to starting a publishing company for my own stuff – and I know Louisa would approve. 🙂

Wonderful story! Louisa was very concerned about her reputation despite her rebellious tendencies; there was a constant tension, almost like a battle between her unconventional and her conventional self.

You are certainly right that creative activities come more easily when worry over money (or even money itself) is removed from the equation. We all forget too that Louisa did lead a domestic life, becoming a mother in her later years when she was given Lulu.

I would love to have guest posts from writers such as yourself about what it’s like for you and how Louisa helps you. Any of you who write for a living or aspire to be a writer or are in the middle of a project – please write to me at louisamayalcottismypassion@gmail.com and let’s talk about some guest posts. I have been far too negligent of this community and the wonderful talent here and would love to share it on this blog.

What type of review are you looking for? I’m flattered that you thought of me.

Just write down what you think of The Relevance of Louisa May – whether you recommend it. Summarize the story and point out those things in it that grabbed you. 600-800 words should be sufficient. As a librarian, you bring a unique point of view. Write to me at louisamayalcottismypassion@gmail.com with any questions and/or to send me your review.

I agree 100% with Gina and could have written her comments myself, minus the money. Though even today, a woman who does not want to marry and have children is looked at as unusual and told “Oh you’ll change your mind.” I can’t even imagine how hard it was for Louisa. I feel she compromised in allowing Jo to marry. She had Jo marry but chose who would marry Jo (not Laurie as everyone wished). She chose a “funny” match for Jo that reflected the morals she wanted to convey. I am one who feels Jo lost herself when she married. Not as much as Anne Shirley did (ugh Anne of Ingleside makes me cringe) but she did give up her identity as Jo March to become the mother of the school. She’s the one who gives Daisy a stove to make pies for the boys. I would rather have seen Jo remain a spinster like her creator but I understand why it was necessary to marry her off and domesticate her. She gets some of her identity back in Jo’s Boys once the boys are grown.

Understood. I gather the thinking of those like you and Gina who feel Jo was compromised think that somehow she lost her freedom which in effect, caused her to lose herself. She was unlike her real self who was a single and free to write. But just how free was Louisa? I see her as hopelessly tethered to her family, the need to make money (even when there was no longer a need) and propriety. Most of all, she was a slave to fear. The psychological scars she suffered in childhood with abject poverty and the turmoil of her parents’ marriage plus her inability to fit in anywhere were hard to overcome. She grew up strong yet very conflicted, torn between what she wanted to be and what she felt she had to be.

Creatively, she boxed herself into a corner. She fell into a line of work that paid well and gave her fame and acceptance–these were hard to resist. That choice I believe limited her as an artist and as a woman. Success created its own kind of bondage.

I would contend that the only time that Louisa was truly free in her life was during those 14 days that she spent in Paris with Laddie. She had a fling with the younger man who was really a boy, thus freeing her from any kind of a romantic commitment (though that didn’t stop May from marrying a man 17 years younger than she). In progressive Europe where no one knew her, she was free from the constraints of propriety. She also could end the relationship whenever she wanted. She was also free from money worries and from taking care of her parents while she was in Paris. It was one of those rare times when she let go, basking in the total acceptance of who she was by a handsome young man.

Back to Jo. It’s true, she did not turn out as her creator wished she had. There was compromise but that is the way life is. There is never a perfect scenario. While I am no expert on Louisa’s books, I can tell when she is writing from the heart and when she is following the formula. Jo’s evolution in Chapter 42 felt authentic to me, and logical. Louisa worked out a good compromise, at least to this reader.

But this is the beauty of this book, yes? That after so many years we can still have such a wonderful and spirited discussion about Jo is a testament to Louisa’s brilliant writing from the heart.

I find Louisa to be a constant source of fascination precisely because she was conflicted and she struggled greatly. I share with her that artist’s temperament, the conflict and joys of the creative life. She has taught me a lot about myself and has always been there when I needed someone that I could relate to when I was going through a difficult time. She continues to be my muse and my hero because she is just so damn human!

You all rock! This is such a wonderful discussion; the very essence of this blog. Thank you!

My first thought regarding the question of whether Louisa May Alcott “sold out” when she married Jo to Professor Bhaer and had her start the Plumfield school for boys is – it depends on what she would have done had there been no other considerations other than what she wanted to do with her own characters: if she didn’t think about money, her audience, the success of the book, her family, what would she have chosen to write of the life of Jo March? What would Jo March have become? If there had been no clamours for Jo to marry Laurie? If there hadn’t been such an expectation in her society for women to marry? If her father hadn’t been so heavily involved in propagating his particular brand of education? Would she still have chosen to write that ending? As has been said it’s well documented that she had planned for Jo to remain single (actually she was astounded by the success Part 1 of Little Women received, so whether she expected to write a sequel could also be debated). And I do agree with your point Susan that Jo March did do something splendid with the school, after all. Not all splendid achievements are necessarily the glamorous ones. But would it have been the story she would’ve written for Jo March, had she been thinking solely of considerations of the plot she wanted? And I’m not sure it would have.

I recently read Eva LaPlante’s Marmee and Louisa (would recommend! Found it a great read and insightful from a writer descended of the Alcotts), and the impression I got from this book was that Louisa’s personal ambitions were for her writing to achieve the sort of success that would allow her to provide for her family, and to have plenty without a care for money. She was involved in nursing, her mother was involved in political causes, and I feel that if Jo March had truly followed the trajectory of Louisa’s life, Little Women might have contained elements of these – but essentially centered on a career as an author. With the obvious demand for a match between Jo and Laurie from the majority of her audience, if she had been writing only for money, that would have been the ending that would have made sense, financially – I wonder sometimes if Little Women might have achieved the popularity of Pride and Prejudice, had Theodore Laurence returned to Jo March with a second proposal as Darcy did with Elizabeth.

But that’s not the ending she wrote, and my suspicion is that she wrote Jo into a school and married to a Professor for the sake of her father – she pleased her publisher and readers enough to marry Jo off (though not the most popular pairing, at least Jo was married) and featuring such a school in her popular books would be a boost for her father’s career agenda (who by this point had become known as Louisa May Alcott’s father, rather than she being known as Bronson Alcott’s daughter). Could this be called “selling out”? I wouldn’t go that far – but I can’t help but feel that Jo’s castle in the air remained that until the end, and that Louisa’s did also – a life of travel and writing that would change the world.

Yes, Louisa was totally bound to her family and their support to the detriment of her art, I think. Yet I doubt she would be remembered today had she written what she truly wanted to write. I recently read a biography of a forgotten 19th century woman author, Constance Fenimore Woolson (Anne Boyd Rioux is the author, fascinating book!) who wrote exactly what she wanted and was quite successful in her time but quickly forgotten upon her death. Somehow Louisa managed to tap into a universal message in a unique way that still spoke to a mainstream audience. It was quite accidental with Little Women and she kept capitalizing on it until it became a well-worn formula where she felt trapped as an artist. Success is not always what it’s cracked up to be, apparently!

That’s a really interesting point you make in that perhaps Louisa might not have written the memorable and unique pieces she had, in quite the way she had written them, were she writing what she truly wanted to write – I’d never thought of it that way. I suppose I had always thought that were she given free rein to write what she would, her writing would have been more powerful, and more impacting, rather than less – but there are of course several instances of talented writers, and pieces of writing, that do not receive the fame or reception proportionate to their quality, and it’s very possible that Louisa might have become such a writer – that had she gone the route of Austen or Bronte with the romances in Little Women, she might have been even more beloved. But perhaps it would not have been simply a matter of being loved more – just beloved by different people, for different reasons 🙂

I used to be a songwriter before I started writing books and I found that the best songs often were those assigned to me to do. I wrote songs for church and sometimes I’d be asked to write about a particular scripture passage or theme and those songs done as a “job” often came out the best. Go figure. 🙂 I suspect maybe Louisa had that experience too. But I do think at some point she needed to break away from the “job” aspect of it to grow as an artist.