Louisa May Alcott has legions of fans worldwide because of a book published in 1868 that targeted younger readers. The author drew heavily upon her family history to create this coming-of-age story that has been cherished and passed down from generation to generation. Yet, the author is far more complex than the book would suggest.

Over the years, scholars have uncovered much information about Alcott’s work beyond that of a children’s author, beginning with her service as a Civil War nurse, leading to the writing of Hospital Sketches, Alcott’s first commercial success. In 1942, literary sleuths Leona Rostenberg and Madeleine B. Stern discovered the pseudonym (A, M. Barnard) Louisa used to keep family and friends in the dark about her numerous gothic potboilers.

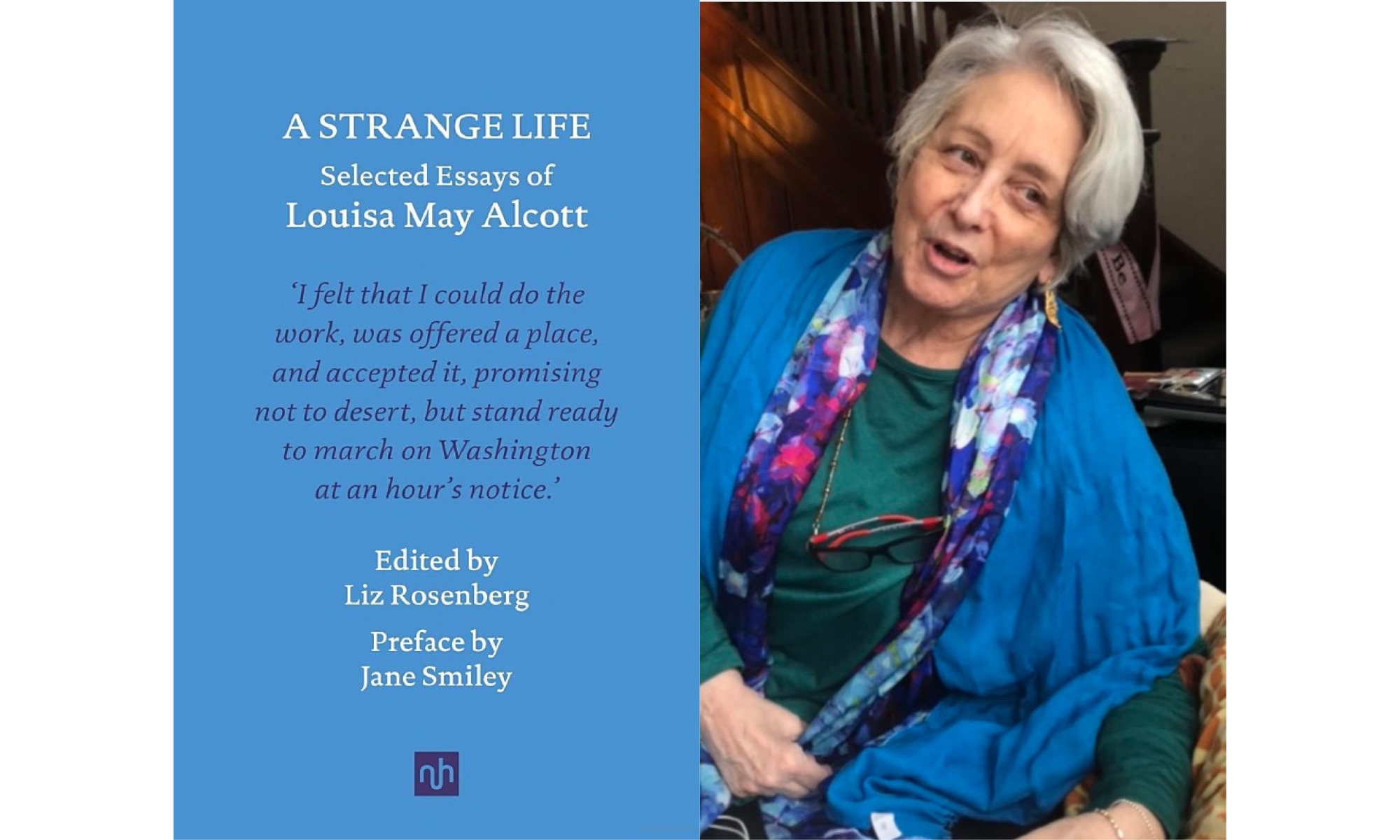

Author/editor and scholar Liz Rosenberg takes a new approach with her latest book, A Strange Life — Selected Essays of Louisa May Alcott, focusing on writing that uncovers much about the author’s use of autobiography, fiction, and truth-telling to tap into a reader’s deepest emotions.

Author/editor and scholar Liz Rosenberg takes a new approach with her latest book, A Strange Life — Selected Essays of Louisa May Alcott, focusing on writing that uncovers much about the author’s use of autobiography, fiction, and truth-telling to tap into a reader’s deepest emotions.

At first glance, knowledgeable Alcott enthusiasts may question why a book (Hospital Sketches), a short story initially dismissed by a famous publisher (“How I Went Out to Service,” and a satire (“Transcendental Wild Oats”) could be considered “essays.” In this engaging conversation, Professor Rosenberg explains her thinking behind identifying these works as “essays” and what they divulge about Louisa May Alcott’s character and genius.

SB: What compels you to characterize Hospital Sketches as an essay? Usually, the book would be considered autobiographical fiction, like Little Women. How did Alcott’s point of view as a woman make Hospital Sketches such a compelling read for those hungry for information about the soldiers? Why does the book continue to speak to readers?

LR: Well . . . Louisa did not think of Hospital Sketches as fiction. She considered it a collage of memories, “topsy-turvey” letters written on top of oil drums–scraps. She goes to some pains to make it clear to the reader that this Union nurse, Periwinkle, really did exist, that this upside-down war hospital really housed the dead, the dying, and the healing. The problem is she asks us to believe this while using crazy, made-up names. But she was a genre-bender at her very best.

As she said of Little Women, “We lived it.” That, she believed, gave the novel its power. She knew it was rooted in autobiography, in reality. In fact, when she published her first book of fairy tales as a teenager, she promised her mother that she would turn time from fairies to “men and realities.” And so she did.

She lived Hospital Sketches; the book began as excerpts of letters home and journal entries. I never read anyone’s memoir as strictly non-fiction per se., because it never is. That’s not how we remember things– we seldom remember conversations verbatim or accurately. We retell “our stories,” so they sound better, funnier, scarier – so they make better stories.

SB: “How I Went Out to Service” is ahead of its time, focusing on the female domestic experience as legitimately important. It is also infamous because of the reaction of James T. Fields, editor of the Atlantic Monthly (“Stick to your teaching, Miss Alcott, you can’t write!”), which ultimately fueled Louisa’s ambition. What does this essay say about the female experience in the mid-19th century? What did Alcott show in this essay about her service experience? Could this essay be considered a precursor to her potboilers because of how she unveiled Josephus as menacing even as he came across as a well-respected community member?

LR: I think that Alcott’s initial image of Josephus – based, of course, on her real-life employer, a lawyer in Dedham – that image of his large hands clad in black leather– that is the stuff of gothic horror, isn’t it? But it’s a hundred times more subtle than her potboilers. I’m not a huge fan of the potboilers; I think they were a guilty pleasure for her, like reading Vogue or listening to bad rap. It filled a void for her, a need to not always be “The Children’s Friend” in an era of great sentimentalism. She was, in fact, the children’s friend in a much deeper way by giving them stories that felt real and true, creating imperfect young characters, giving charity to young working women and children, writing about working-class girls and women, encouraging young writers; supporting female-run businesses . . . so many things.

A lot of people want to sugar-coat Louisa May Alcott, the same way they’ve sugar-coated Emily Dickinson – “Come look at her tiny white buttoned-up dress behind glass; come admire Louisa’s half-moon desk in one nook of her shared room,” while Bronson has the regal study downstairs filled with all the books. But Louisa never tried to sugar-coat herself in these essays. That’s one of the many things I love about her. She was a truth-teller when she created stories and a story-teller when reporting the facts. Genius won’t be neatened up and pinned down.

SB: “Transcendental Wild Oats,” Alcott’s essay on the Fruitlands experiment, demonstrates her mastery of satire (her coping mechanism) to describe the most devastating circumstances. It showcases how Alcott communicated so well with her readers by digging deep into a wide range of emotions, whether anger, poignancy, or sarcastic humor. Even though this utopian community proved stranger than fiction, readers could relate. It’s the magic formula she employed so brilliantly in Little Women. What do you think her purpose was in writing this essay? What did she want her readers to know?

LR: “Transcendental Wild Oats” was the last of her three most famous essays, though the events it records are the earliest. I find that interesting. I think it took her a long time to process what had happened — and worse, what had almost happened — to the Alcott family when she was ten years old and moved to that Godforsaken commune. It’s a story that involves lunacy, starvation, betrayal, sexuality, failure, and a nervous breakdown — yet I would agree that it’s the funniest of her essays. It may be the funniest thing she ever wrote, period. It’s wild and satirical and tender and fierce and hilarious by turns. I don’t think anything, even in her best novels, can touch it.

LR: “Transcendental Wild Oats” was the last of her three most famous essays, though the events it records are the earliest. I find that interesting. I think it took her a long time to process what had happened — and worse, what had almost happened — to the Alcott family when she was ten years old and moved to that Godforsaken commune. It’s a story that involves lunacy, starvation, betrayal, sexuality, failure, and a nervous breakdown — yet I would agree that it’s the funniest of her essays. It may be the funniest thing she ever wrote, period. It’s wild and satirical and tender and fierce and hilarious by turns. I don’t think anything, even in her best novels, can touch it.

Like all great ones, the comedy of Alcott had its roots in sadness. It was also rooted in humiliation. She had weathered so many humiliations early on– poverty, indebtedness, taking in sewing, laboring through the night, doing the hardest and humblest of household tasks, fending off rejection, both social and literary. Her family was the black sheep of the May family (her mother’s side) — the laughingstock of Concord. I think her survival depended on being able to laugh at herself. She was a remarkable survivor, don’t you think? [SB: Yes!]

SB: Alcott’s essays blend autobiographical facts with fiction to explore truths about everyday life. This style reached its apex with the writing of Little Women. Why do you think she employed fiction in her essays, and do you think her use of it heightened the emotional impact of her writing? If so, how?

LR: Alcott used fiction in her essays and reality in her fiction. As the great novelist John Gardner once wrote, the best fiction is usually “mutt” fiction this way, a combination of things that don’t seem to go together — Edgar Allen Poe and Gabriel Garcia Marquez; Samuel R Delaney; Virginia Woolf, Jane Austen, and Charles Dickens—horror stories and supernatural events and detective novels, romances and science fiction and human psychology. Shakespeare was the most remarkable mutt of all. He was a mix of everything — poetry and tragedy, vulgar comedy and violence, medicine and law and history. You can’t pin it down to one thing in his work because it’s a hundred things– he’s a hundred things. Louisa was like that, too. All deep thinkers are. And Alcott was nothing if not a deep thinker.

A Strange Life — Selected Essays of Louisa May Alcott is available through Amazon and other online outlets.

Are you passionate about

Are you passionate about

Louisa May Alcott too?

Subscribe to the email list and

never miss a post!

Facebook • Instagram • Twitter

Find Susan’s books here on Amazon

Find Susan’s books here on Amazon

Thank you so much Susan, for sharing this coversation with us.

All my Best Wishes and Regards.

Alex L.