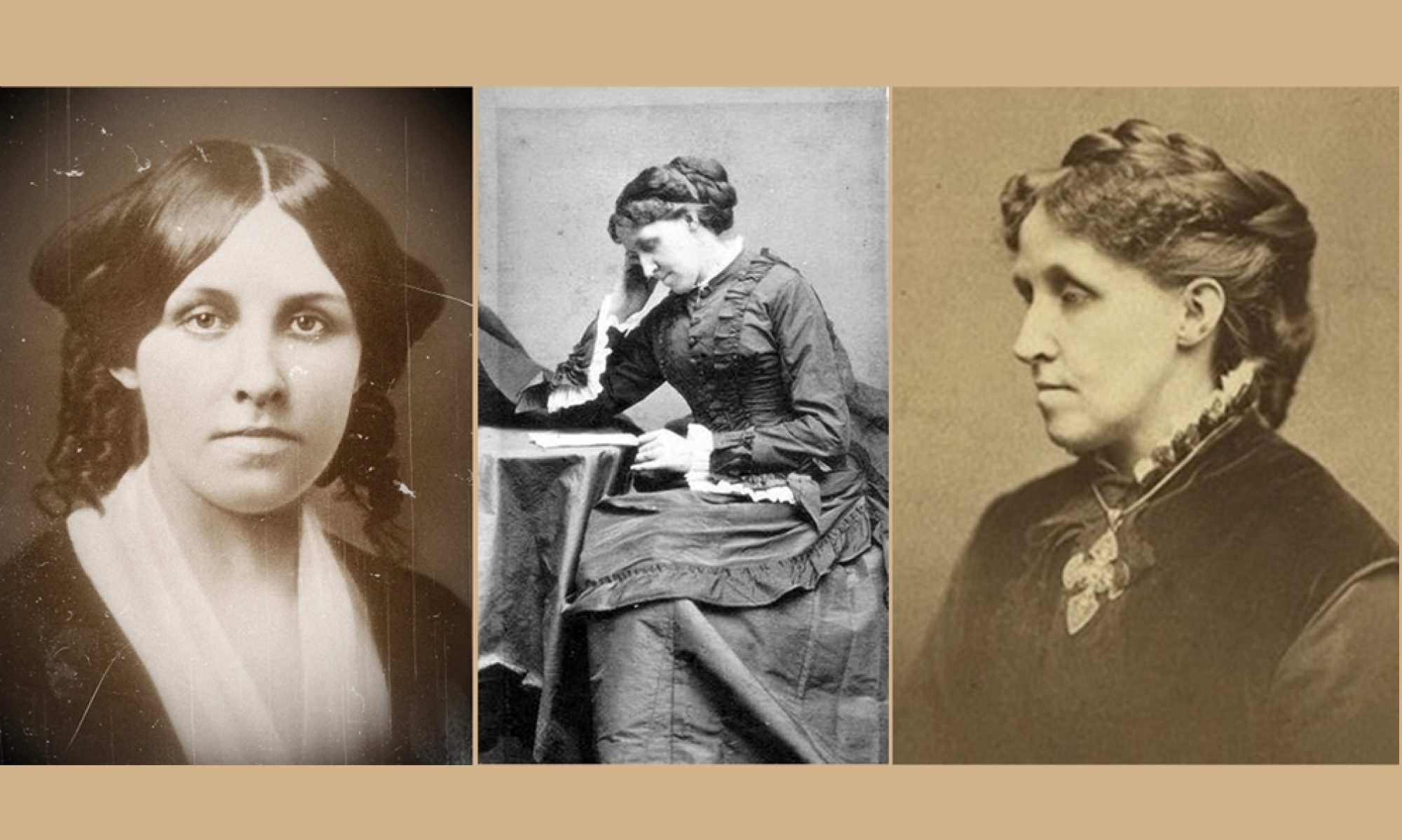

As a writer, army nurse, single mother, caretaker and homemaker, the celebrated author of Little Women blazed a trail for women managing home and career.

When people hear the name of Louisa May Alcott, they think of Little Women. A novel written for girls, this best-selling classic celebrates the home, marriage and motherhood. It also champions women achieving autonomy, carving out lives of meaning and purpose apart from the home. Alcott said of the book that “we really lived most of it.”[1] She fashioned her characters after her immediate family with Jo representing herself. Both she and Jo harbored great ambition while at the same time, fulfilling their domestic duties. Alcott remained single, becoming head of the household while Jo married and had children. Yet Jo insisted on a partnership in her marriage to Professor Bhaer saying, “I’m to carry my share, Friedrich, and help to earn the home.”[2] Together they ran the school at Plumfield for boys; in later years, Jo became a successful author.

Louisa and Jo juggled multiple roles: Jo as wife, mother, help mate and author, and Alcott as breadwinner and businesswoman, homemaker, caretaker of her parents, single mother to her niece Lulu, and of course, author. She also served for a brief period as a Civil War nurse before being afflicted with typhoid pneumonia. Alcott defied Victorian convention by assuming both male and female roles so she could provide for her family as well as care for them. Thus, one of Louisa May Alcott’s major contributions to feminism was in blazing a trail in the management of career with family and the home.

Assuming the mantle early

Alcott anticipated her role as provider early as she witnessed the difficulties her mother endured. Bronson Alcott, a relentless idealist, was either unwilling or unable to support the family. Chronic poverty was the result with his wife, Abigail, often reduced to begging for help from wealthy relatives as she struggled to bring in money. Earning opportunities for women were limited to low wage domestic jobs (governess, seamstress, laundress, servant) or factory work. Ten-year-old Louisa committed herself to her mother’s care in a poem written in her journal.[3] Many years later after Mrs. Alcott’s death Louisa annotated her entry: “The dream came true, and for the last ten years of her life Marmee sat in peace, with every wish granted.”[4] This dream proved to be the driving force of Alcott’s professional life.

Alcott anticipated her role as provider early as she witnessed the difficulties her mother endured. Bronson Alcott, a relentless idealist, was either unwilling or unable to support the family. Chronic poverty was the result with his wife, Abigail, often reduced to begging for help from wealthy relatives as she struggled to bring in money. Earning opportunities for women were limited to low wage domestic jobs (governess, seamstress, laundress, servant) or factory work. Ten-year-old Louisa committed herself to her mother’s care in a poem written in her journal.[3] Many years later after Mrs. Alcott’s death Louisa annotated her entry: “The dream came true, and for the last ten years of her life Marmee sat in peace, with every wish granted.”[4] This dream proved to be the driving force of Alcott’s professional life.

Louisa’s days as a wage earner began at eighteen with the family’s move to Boston in the late 1840s. While teaching school, doing laundry for wealthy cousins, acting as a servant for a man and his invalid sister, and sewing, she wrote in her spare time, submitting to newspapers and magazines. She recorded her earnings in 1850, establishing a lifelong habit of meticulous bookkeeping.[5]

Writer of all trades

As a writer, Louisa May Alcott approached her art in a utilitarian manner. An astute businesswoman, she catered her stories to the marketplace, maximizing her profit margin. When Little Women was accepted for publication, Thomas Niles of Roberts Brothers offered her ownership of the copyright in lieu of a one-time payment. It was a gamble that paid off, making her a wealthy woman. She continued this practice with subsequent books. To keep the copyrights from expiring, she adopted her nephew John Pratt and named him as her heir, assuring income for the next generation.

Alcott wore many hats as a writer. Flower Fables, written when she was a teenager, consisted of fantasy stories featuring fairies and elves. Later, professing an attraction for the “lurid,” she wrote thrillers and suspense tales for illustrated newspapers. Titles such as “Pauline’s Passion and Punishment,” “A Marble Woman” and “Behind a Mask” featured revengeful women, violence and drug use. Using the pen name of A. M. Barnard to protect her reputation, Alcott supported her family for several years with what she deemed as “trash.” After her service in the Civil War, she adapted the letters sent home to her family into in her first commercial success, Hospital Sketches. In in the late 1860s she entered the burgeoning children’s market as editor of Merry’s Museum; it was at this time that Thomas Niles of Roberts Brothers commissioned from Louisa a book for girls. Alcott undertook the writing of Little Women under duress with the promise that her father’s book would too be published if she complied. That sense of duty ended up fulfilling the long-held dream of a permanent end to her family’s poverty.

Finding meaning in housework

Alcott found ways to combine her writing with her household tasks, simmering stories in her mind as she cleaned house and cared for ailing family members, and later putting down her ideas on paper during quieter moments.[6] A robust woman especially in the first half of her life, Louisa preferred physical labor such as scrubbing floors and washing clothes as those tasks left her mind free to create stories, whereas teaching and sewing required more mental concentration.[7] Subject to moods, she wrote that “work of head and hand is my salvation when disappointment or weariness burden and dark my soul.”[8]

Her journals over the years are filled with references to household tasks. Along with sweeping, scrubbing, pounding rugs, cooking and sewing, she saw to it that the roof was repaired and the house painted. Housework proved helpful whenever she experienced writer’s block: “Must wait and fill up my idea- box before I begin again. There is nothing like work to set fancy agoing.”[9]

Her journals over the years are filled with references to household tasks. Along with sweeping, scrubbing, pounding rugs, cooking and sewing, she saw to it that the roof was repaired and the house painted. Housework proved helpful whenever she experienced writer’s block: “Must wait and fill up my idea- box before I begin again. There is nothing like work to set fancy agoing.”[9]

First-time mother; long-time caregiver

Alcott’s mid-forties and fifties proved to be particularly challenging when it came to juggling work with domestic responsibilities. In 1877 Abigail began to fail, suffering from congestive heart failure. Along with nursing her mother, Louisa found time to finish both a short story and a children’s book.[10] At forty-seven she adopted her little niece Lulu, the daughter of her recently deceased sister May. Lulu infused Louisa with new life, helping her through her grief over the sudden death of May. Journal entries describe Alcott romping with Lulu, throwing lavish parties and holding the child in her arms while telling stories, many of which ended up in a published collection, Lulu’s Library.[11]

In 1882 Bronson suffered a debilitating stroke and required round-the-clock care. Because of her work commitments along with her own declining health, Alcott hired governesses and nurses to help. Her journal is peppered with complaints about the difficulties of finding good help.[12]

Good results and the high cost

Louisa May Alcott was successful in juggling her many roles but not without cost. Her health, never the same after the bout of typhoid pneumonia and subsequent mercury poisoning, declined precipitously, aggravated by chronic overwork. She died at the age of fifty-five in 1888 after years of suffering.

Master juggler

Louisa May Alcott’s candor in her journals demonstrates what women today already know: managing career and home is never easy, and can exact a high price. Alcott succeeded, proud of her accomplishments as author, breadwinner, mother and caretaker. She made her choice with stoic determination as she wrote, “This double life is trying and my head will work as well as my hands.”[13] As a result of reading Alcott’s books and studying her life, countless women have pursued their calling of authorship while maintaining a home. One hundred and thirty-seven years after her death, Louisa May Alcott continues to inspire women around the world.

[1] Louisa May Alcott (author), Joel Myerson, (editor), Daniel Shealy (editor), Madeleine B.Stern (associate editor), The Journals of Louisa May Alcott (The University of Georgia Press, 1998), page 166, August 26, 1868

[2] Louisa May Alcott, Little Women (Penguin Classics 1989), pg. 480

[3] Ednah D. Cheney, Louisa May Alcott Her Life, Letters and Journals (Roberts Brothers, 1891), page 24

[4] Ibid

[5] That year she made $50.10 for teaching and $10 for sewing. She also sold her first story, “The Rival Painters,” for $5. Journals pg. 64, ‘Notes and Memoranda’

[6] Journals, page 90 August 1858

[7] Louisa May Alcott (author), Elaine Showalter (editor) Alternative Alcott “How I Went Out to Service” (Rutgers University Press, American Women Writers, 1994), page 352

[8] Journals, page 91 November 1858

[9] Journals, page 128 February 1864

[10] Journals, page 205 September 1877, The story was “My Girls,” and the book, Under the Lilacs. Adversity did not deter her pen: “Brain very lively and pen flew. It always takes an exigency to spur me up and wring out a book.”

11] Journals, pages 233 March 1882, 244 April 1884

[12] Journals, page 239 May, June 1883

[13] Journals, page 238 February 1883

Are you passionate about

Are you passionate about

Louisa May Alcott too?

Subscribe to the email list and

never miss a post!

Facebook • Instagram • Twitter