Better late than never, I finally finished An Old-Fashioned Girl! And I have lots to say about it through several posts in the next few days.

I have already written a few posts about this book which you can find here.

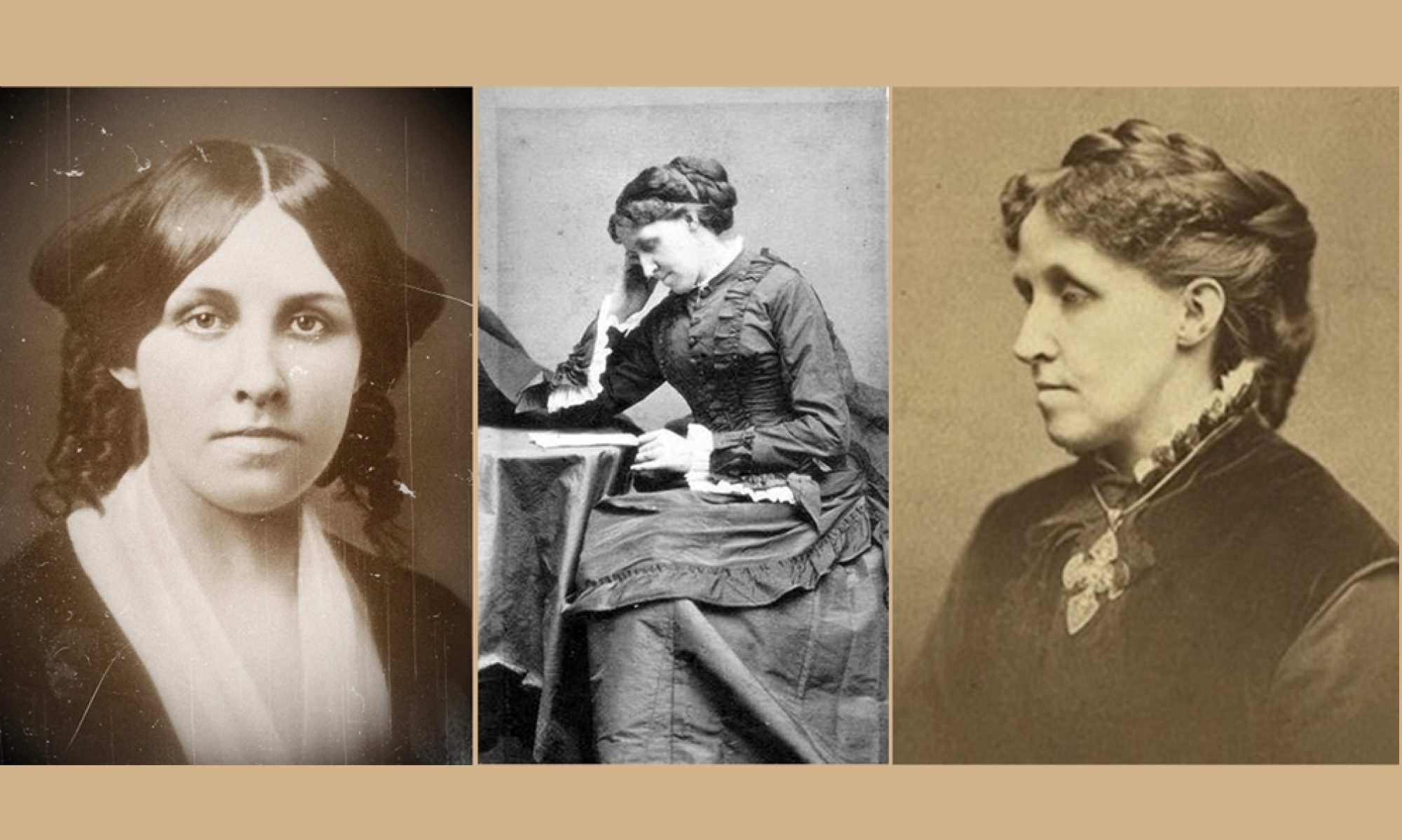

I have to admit that the book lost me somewhere in the middle, before the story transitioned into Polly’s adult life. What brought me back in was a combination of listening to chapters at work (thanks to Librivox), and the discovery of Victorian Domesticity – Families in the Life and Art of Louisa May Alcott by Charles Strickland at the Concord Free Public Library. This book was a godsend, filling in all those historical gaps which helped me to understand the context of this book, and all of Louisa May Alcott’s writing (I will be writing more about this book when I finish it).

In Chapter 7, Polly ends her long visit with the Shaw family and heads on back home. Louisa then moves the timeline up in chapters 8 and 9 by 6 years so that 14 year-old Polly is now 20 and a working girl. We find Fanny as a 22 year-old lady of fashion, somewhat dissatisfied with her life. Tom is off at college, and Maud has turned 12.

Here’s where the story got interesting. It was not hard to read between the lines and see what Louisa’s core beliefs were about women, men, and families both wealthy and poor. And Strickland’s book offered great background into life in 19th-century America.

Chapter 9 opens describing Polly’s life as a working girl, teaching music to individual students. Her days are long, and her life is lonely. The “friends” she made through Fanny shun her because she works. Poor Polly even believes that Tom has snubbed her although that was because of Trix, Tom’s fiance (and a classic portrait of the lady of fashion that Louisa so disapproves of – more about that in later posts).

Reading this chapter reminded me of the first time I saw a classic Joan Crawford movie, “Mildred Pierce,” made in the 1945. In the movie, Mildred has been dumped by her husband and must go out to work. She has a talent for cooking and eventually gets so good at it that she opens her own restaurant. By midway through the movie she is somewhat of a restaurant tycoon, owning a small chain. By today’s standards, she is a smashing success and worthy of praise.

But in the movie, she is treated as a second-class citizen by all who know her, most especially her incredibly spoiled and bratty daughter, Veda who believes her mother to be “common.” (There is much more to this movie and I highly recommend it – great film noir).

But in the movie, she is treated as a second-class citizen by all who know her, most especially her incredibly spoiled and bratty daughter, Veda who believes her mother to be “common.” (There is much more to this movie and I highly recommend it – great film noir).

I was surprised at the parallels between Polly’s experiences in the 1870s and Mildred’s in the 1940s, telling me that not a lot had changed. It’s really over the last 50 years that women have begun to be regarded favorably because they work (that’s my generation!).

While the baby boomer generation has come under a lot of criticism of late (much of it justified), we did achieve much greater autonomy for women. My daughter’s generation is the first to truly benefit. Yet, they don’t know the history and the struggle that women have gone through to achieve these ends, and they take their new-found freedom for granted, even squandering it!

How ironic. And it’s ironic too that Louisa probably would not be pleased at the ways of society today. As women have been navigating that oh-so-tricky road of trying to “have it all,” the family has suffered. There is confusion for women and for men regarding their roles, and much still needs to be worked out.

Louisa, however, thought the nuclear family sacred. This belief runs through all of her juvenile writing as seen in Little Women and in An Old-Fashioned Girl.

She also, however, believed that women needed to find purpose in their lives, rather than live the life of fashion (as Fanny was doing, and she was increasingly unhappy with her rudderless life). Polly found that purpose in her work, and also, in her desire to do all she could to help the Shaw family discover what they were missing in their family – appreciation and love for each other. It was the perfect balance of Louisa’s beliefs – work is good in providing purpose and meaning, and tending to the family with complete devotion also brings purpose and meaning.

According to Strickland in Victorian Domesticity, An Old-Fashioned Girl had some pretty radical ideas about women, albeit gently presented. It amazes me how Louisa’s juvenile works were so widely read and loved and makes me wonder if the public actually read between the lines. Yet I imagine the message got through in a subliminal fashion, which was her intention. And she called this moral pap! Louisa was pretty darn clever.

More to come . . .

Are you passionate about Louisa May Alcott too?

Send an email to louisamayalcottismypassion@gmail.com

to subscribe, and never miss a post!

Facebook Louisa May Alcott is My Passion

More About Louisa on Twitter

I’ve read a lot and written a lot about nineteenth century women. Send me an e-mail and I can send you a bibliography of some newer books to look at or an annotated bibliography showing how the scholarship on reading/writing/working women has changed over the years.

QNPoohBear<— history major

Haha LOVED your comparisons to Mildred Pierce 😉

Mildred Pierce is one of my favorite movies all time. Joan Crawford was amazing. Kind of wish I hadn’t seen “Mommy Dearest” though!

I know what you mean. But honestly, much of Mommy Dearest was blown so out of proportion by her daughter who resented Joan cutting her out of her will.

It was a very strange story, for sure!