Guest post by Lorraine Tosiello

Louisa May Alcott had been dead for nearly a century before her reputation changed.

It was 1975 when Madeleine Stern released a collection of Alcott’s sensational thrillers (1). With the discovery of titillating stories of revenge, psychological manipulation, and women scorned and vindicated, it was clear that Louisa May Alcott had led a double literary life. Today, these stories are viewed as significant works of feminism in counterpoint to, or perhaps in collusion with, the more famous Little Women. Although Little Women has been interpreted theatrically, on film, as an opera and a television serialization (2), the gothic thrillers have received little attention regarding adaptations.

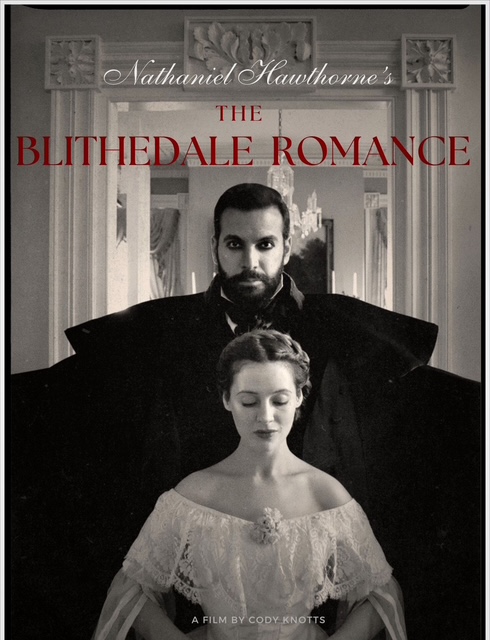

Until now. Enter Cody Knotts and Emily Lapisardi, the creative team behind Eternity Box Films, an independent studio devoted to bringing early American Gothic novels to life. Having just wrapped up production of The Blithedale Romance, they have their sights set on Behind a Mask, possibly the most beloved of Alcott’s previously unknown stories. Behind a Mask was written under the pen name A. M. Barnard and never linked publicly to Alcott during her lifetime. With the Eternity Box’s reputation for psychologically thrilling and lushly costumed films, I suspect Alcott herself would be radiantly joyful that her “hidden” work- her complex, theatrical, emotional work- will be brought to life with a faithful and extraordinary production.

I was able to ask Cody Knotts and Emily Lapisardi about their creative choices and their understanding of Alcott’s work and legacy.

- Tell us about your production company, Eternity Box Films, and how your mission is to adapt nineteenth-century American novels.

Eternity Box Films is an independent studio undertaking a planned series of eleven productions based on classic literary works of the long nineteenth century, none of which have been adapted into feature films. We have a particular interest in cinematic adaptations of early American Gothic novels: our first film in the series was Charles Brockden Brown’s Wieland, now available through several streaming services, and we are currently completing post-production on Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Blithedale Romance. Hollywood studios, for the most part, now show little interest in faithful adaptation of literary works; while such productions were popular decades ago, many of the major production companies now feel that they do not provide sufficient return on investment or have a wide enough audience to merit development. American International Pictures and Hammer Studios used to make films based on Gothic literature on relatively limited budgets, but with an emphasis on production values, and these precedents serve as inspiration for Eternity Box Films. As an independent studio, we specialize in this particular niche; we can lower production costs by focusing on a specific genre and period. Our tagline is “history, mystery, and memory.”

- You both come from eclectic professional backgrounds; journalism and politics on Cody’s side, theater, music, and historical costuming on Emily’s side. This seems to be the perfect storm of talents to create a film, but how did this amalgamation of talents finally express itself in filmmaking?

Cody produced and directed his first feature film in 2011. He initially set out to write a script based on his experiences as an investigative reporter, but was still too close to the subject matter to complete that project. Instead, his first several films were all horror movies rooted in sensationalism and pop culture. For over twenty years, Emily has presented first-person portrayals of historical figures for museums, educational institutions, and historical societies in fourteen states and Washington, D.C., and had previously played the leading role in the Civil War era biopic Spies in Crinoline. When we married in 2014, we also began to collaborate creatively. As the daughter of a literature professor and a high school English teacher, Emily was particularly intrigued by the prospect of literary adaptation, and we both share a love of history. By combining our interests and areas of expertise, we hope to make films that have enduring value and state something about the human condition.

- Your approach to adapting these classics incorporates collaboration with academics and scholars of the period. Describe this unique process of scholars advising your work.

While we were in production on Wieland, we reached out to the Charles Brockden Brown Society and were incredibly pleased with the scholars’ willingness to advise us– and the Society’s invitation to us to present on the process of adaptation at their conference. We assembled a team of advisors even sooner in the process for The Blithedale Romance; scholars from the Hawthorne Society, the Margaret Fuller Society, and the Communal Studies Association (an organization from which Emily had previously received a fellowship for her research on the hymnody of the Harmony Society) were involved in pre-production: they attended Zoom discussions and rehearsals, gave feedback on various iterations of the script, and even worked with the production design team to create a meticulous prop version of The Dial for use in the film. Each of the leading actors was paired with a literary advisor specifically for their character; as Zenobia, I [Emily] was especially grateful for the advice of Dr. David Diamond, who is both a Hawthorne scholar and a psychoanalyst! The Blithedale advisory team included fourteen scholars from noted institutions in the U.S. and abroad and several experts on mid-nineteenth-century material culture. As we begin developing Behind a Mask, we are working to assemble a similar advisory panel willing to contribute expertise based on years of specialized research. Our adaptations are intended for a literary audience, and we hope that they will be used in collegiate courses that study these works and those that discuss the process of literary adaptation. Many film adaptations of beloved works fall short of readers’ expectations because the production disregards both the fans and the experts—we want both groups to be actively involved!

- When creating “The Blithedale Romance,” did you recognize any new appreciation for or anecdotes about Concord?

We knew that the town of Concord was crucial to our understanding of the world of The Blithedale Romance. While Hawthorne’s “knot of dreamers” is partially inspired by his time at Brook Farm, it also reflects the community of Concord as he knew it—a “genius cluster” of great minds and collaborative creativity. We knew that we had to have “boots on the ground” in Concord to fully immerse ourselves in the milieu of the narrative prior to filming, so we spent several days there for our tenth wedding anniversary in the late spring of 2024. We also shot our Indiegogo promotional video simultaneously, so I wandered the streets dressed as Zenobia and was mistaken for either Louisa May Alcott or Sophia Hawthorne numerous times.

- The Alcotts and the Hawthornes were neighbors, and the Hawthornes lived in the home that the Alcotts had inhabited years before. Do you see the influence of Nathaniel Hawthorne on Alcott’s writing in “Behind a Mask?”

As a keenly observant girl growing up in such a fruitful atmosphere, Louisa May Alcott absorbed a great deal from the other great minds she knew in Concord. I find a particular connection thread in the strong female characters in both Hawthorne and Louisa May Alcott’s works: Hawthorne’s “dark ladies” and Jean Muir have a good deal in common. They defy nineteenth-century stereotypes and are complex, psychologically deep women with rich inner lives and, often, complex life experiences. Alcott was drawing on her own experiences as a highly intelligent woman, of course, but I believe she and Hawthorne were also inspired to create these rich and multifaceted characters by some of the remarkable women they both knew, including Margaret Fuller and the Peabody sisters.

- Many critics of recent adaptations of “Little Women” have faulted the costuming as not appropriate to the time. Your costumes are exceptionally lush and period-perfect. Can you discuss your devotion to that aspect of filmmaking?

I [Emily] have been fascinated with nineteenth-century clothing for most of my life! My mother was trained as a theatrical costumer, so I learned about color theory and design from her very early on. However, when I began to present first-person portrayals of historical figures, we discovered that standards and construction techniques in the living history community are very different than those for the stage. Through the study of original garments, we learned period construction techniques and were able to create museum-quality reproduction garments for my portrayals. My nineteenth-century wardrobe might be bigger than my twenty-first-century wardrobe now, and I’m a proud “thread counter.” With this background and my connections in the living history community, I believe we had an advantage in producing period films that very few independent studios could match. On Wieland, our production designer was the legendary Juanita Leisch Jensen, an icon in the Civil War reenactment community. When the production designer for The Blithedale Romance had to withdraw during pre-production because of a family situation, I took over. This meant that, during filming, I often shot highly demanding scenes as Zenobia during the day and then stayed up all night preparing wardrobe and set dressing for the next day’s shoot. My friends and I love to criticize inaccuracies in period films, but being part of the process has given me a (slightly) more tolerant and understanding view of why films often fall short. Many production designers simply aren’t fashion historians, and when working on a tight time frame and a fixed budget, and with actors who can occasionally be rather demanding about their own preferences above accuracy, you must do the best you can in stressful situations. I believe that our films are far more meticulous than the majority of period pieces, either independently produced or from major studios, but there are still things I wish we could have done differently. I’m planning to serve as the production designer for Behind a Mask as well, but am insistent that we will need a strong wardrobe crew during filming itself so that I can focus on my performance.

- What were the biggest surprises you uncovered in researching Alcott’s gothic stories?

While Alcott’s gothic works have gained some wider currency in recent years, they are still largely unknown among the general public. In them, she shows a willingness to touch darkness that isn’t present in the works of many female writers of the period. In this, she seems much closer to the Brontë sisters than Jane Austen or the best-selling but now forgotten mid-nineteenth-century novelists Susan and Anna Warner. Given her reputation as a children’s author, we were especially intrigued by how deftly Alcott deals with adult themes and ambiguity. Is Jean a heroine or a villain? She achieves her ends through duplicity, yet we root for her.

- Jean Muir is one of the most beloved characters from Alcott’s gothic oeuvre. She can be beseeching and scalding in the blink of an eye. Emily, can you talk about the challenges this character presents?

Jean Muir is the sort of role that most actresses hunger for—and I am both excited and a bit apprehensive to be the first person to portray her in film. She is a skilled actress, so my performance must encompass Jean’s private self, her complex past, and the role she has taken on with the Coventry family. This will require a great deal of nuance and subtlety in both the delivery of the lines and, especially, the non-verbal aspects of the performance. Film must “show, not tell,” and my performance must depict the complex interplay between Jean’s public mask and her private self. However, this is true not only of Jean but also of the other two literary heroines I’ve portrayed in our previous films: Clara in Wieland and Zenobia in The Blithedale Romance. It is both a great honor and a tremendous responsibility to breathe cinematic life into these characters. Unlike Zenobia, however, Jean emerges triumphant at the end—and I’m greatly looking forward to that!

- “Behind a Mask” reads almost like a theatrical script; the “stage directions” are complete. It reflects Alcott’s keen interest in the theater. Does this help or hinder your personal adaptation of the work?

Film and theatre grow from common roots but have diverged in style and approach over the last century: theatre paints with broad strokes while film offers very personal glimpses into the characters’ world. As a teenager, I [Emily] proudly wore a badge proclaiming “Theatre is art, television is furniture,” but I have come to appreciate the cinematic arts much more since then. Behind a Mask is an intimate family drama in many ways, and the medium of film will allow us to explore the characters’ perspectives and how Jean Muir impacts each of them in a nuanced way. That’s one of the reasons we were so drawn to this work—Alcott wrote an incredibly cinematic story prior to the advent of film. The rich details of her writing conjure up images in the reader’s mind. Still, an adaptation must also consider the filming locations’ realities and the camera’s placement in relation to the actors. During filming for The Blithedale Romance, the principal actors and many of the supporting cast and crew carried paperback copies of the book, which we referenced continually throughout the process, especially regarding blocking. I’m sure that will also be the case with Behind a Mask, especially since some of the same actors and production team have already signed on. Our screenplay was partly inspired by the brilliant 1995 adaptation of Jane Austen’s Sense and Sensibility and the classic film All About Eve. While Jean Muir is the book’s most complex and fascinating character, our adaptation will allow other characters, in particular Lucia and Sidney, to step into the foreground as well.

- What do you hope your film will achieve for Alcott’s legacy?

While Little Women has been the basis for multiple big-budget film adaptations, we feel that the breadth of Alcott’s oeuvre is underexplored, mainly in the medium of film. The works of Jane Austen and the Brontë sisters, and their own lives, have been the subject of a whole range of movies and yet Alcott, who in many ways is America’s counterpart to those authors, and who wrote many works which have tremendous potential for cinematic adaptation, has, in large part, been relegated to the role of beloved children’s author in contemporary American society. Her body of work encompasses so much more than that, and she deserves to be more fully recognized for the rest of her output and not as a “one-hit wonder.” We hope our adaptation of Behind a Mask will delight fans and scholars and encourage a broader audience to read her other works.

(1) Alcott LM. Behind a Mask: The Unknown Thrillers of Louisa May Alcott, ed Stern, MB. William Morrow & Co., New York, 1975

.(2) Rioux, AB. Meg, Jo, Beth, Amy: The Story of Little Women and Why it Still Matters, W. W. Norton & Co., New York, 2018.

Are you passionate about

Louisa May Alcott too?

Subscribe to the email list and

never miss a post!

Facebook • Instagram • X